by Zach Dulli, The Scene | Photos by Damon Baker

For many American teenagers, few literary experiences loom larger than being assigned The Crucible in English class. With its potent mix of historical drama, allegory, and scorching indictments of public hysteria, Arthur Miller’s 1953 masterpiece has long been a rite of passage for students grappling with moral complexity on the page. However, those same students become the central protagonists in the new play John Proctor Is the Villain—written by Kimberly Belflower and arriving on Broadway this month. Through their eyes, we see a play we thought we knew turned inside out, revealing fresh and often uncomfortable truths about how power operates and who gets to claim moral authority.

A 21st-Century Lens on a 17th-Century Tale

The Crucible famously dramatizes the Salem witch trials of 1692. Back then, Puritan communities teetered on the edge of chaos as a few well-placed accusations of witchcraft spiraled into a communal panic. The text features John Proctor, typically introduced as a flawed but ultimately heroic figure, forced to weigh self-preservation against telling the truth about the hysteria enveloping his town.

Yet, for today’s audiences—especially those shaped by the #MeToo movement and a keener public awareness of consent—Proctor’s affair with the teenager Abigail Williams resonates differently than it did even a few decades ago. In The Crucible, Proctor’s indiscretion is often portrayed as a moral slip that compels him toward redemption. Now, that same relationship might be read as exploitative, prompting a revision of a central character we once deemed heroic.

A Play About Reading a Play

The structure of Belflower’s work is one of its most intriguing aspects: instead of staging a literal retelling of The Crucible, the young characters in John Proctor Is the Villain are tasked with reading Miller’s text for a school assignment. This meta-theatrical approach transforms the reading process into high drama. In class, the students wrestle with the historical context of Puritan Salem, the language of Miller’s allegory, and the creeping sense that what seems “classic” might also be deeply problematic.

While some students are quick to defend the “complex morality” of Proctor’s character—mirroring the traditional perspective taught in many American classrooms—others refuse to look past his actions. That tension breathes new life into a text that might otherwise feel too familiar. Through the voices of bright, skeptical teenagers, Belflower surfaces the internal debates many readers have had about The Crucible but rarely see staged.

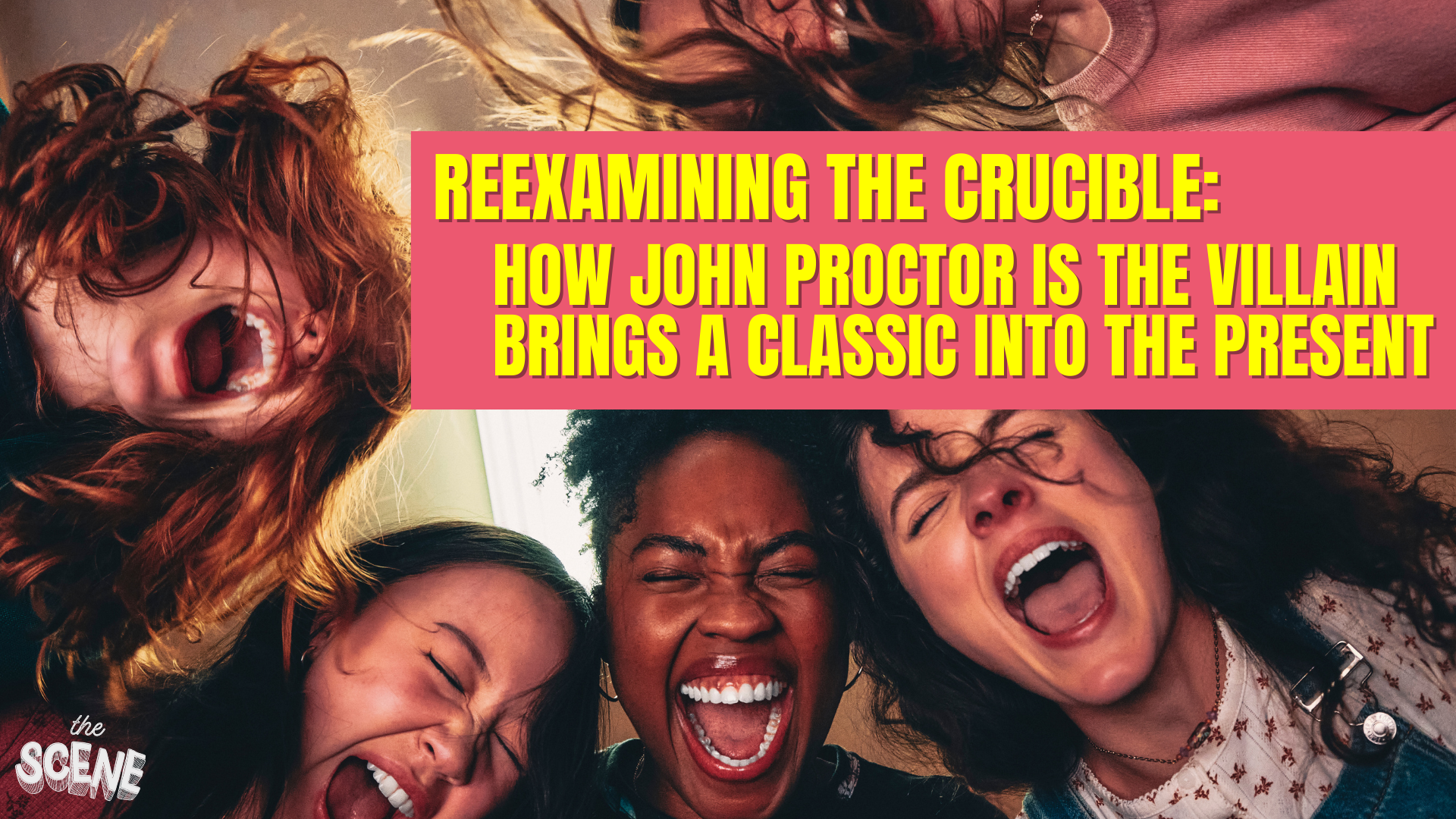

Maggie Kuntz, Fina Strazza, Sadie Sink, Morgan Scott, Amalia Yoo from the upcoming Broadway production of John Proctor is the Villain—photo by Damon Baker.

From Salem to the Modern South

In John Proctor Is the Villain, Belflower also leverages a vividly drawn modern milieu. While Miller wrote about Massachusetts in the 1600s, Belflower situates her story in a present-day Southern community, a place where social norms—especially regarding gender roles, sex education, and reputation—can remain deeply entrenched. This parallel between Puritan Salem and a conservative contemporary town adds to the sense that The Crucible is not just a dated historical piece but a text capable of speaking directly to ongoing social issues.

In Belflower’s rural Georgia setting, the teenagers negotiating these themes carry smartphones, navigate social media, and confront rumors that can spread in seconds—so that real or perceived “scandals” in their world can ignite a panic worthy of Salem. While Miller’s characters fear excommunication and the gallows, Belflower’s face their own forms of social annihilation—suspension, ostracization, or the wrath of a community still shaped by gossip and shame.

An Evolution in Critical Reception

The reevaluation of John Proctor as a “hero” is not entirely new; feminist scholars and progressive directors have, for years, encouraged audiences to question how we center a character who sleeps with a teenage girl. But it’s only in the last decade—spurred in part by new awareness of how power imbalances manifest—that a mainstream audience has begun to shift perspective on the matter.

Since the #MeToo movement, viewers have been quick to question the sympathetic portrayal of characters like Proctor. For some, the shift in perspective can be disconcerting: the role has been played by prominent actors (including Daniel Day-Lewis in the 1996 film adaptation) who bring grave dignity to Proctor’s moral tribulations. Yet for others, Belflower’s direct challenge to this long-standing reading of The Crucible is precisely what makes John Proctor Is the Villain so timely and necessary.

Broadway Beckons

The play’s journey to Broadway has generated considerable anticipation. Broadway, after all, has historically been a site for canonical reexaminations, giving classics a new spin or providing a platform for contemporary works that use classic texts as springboards. Recent revivals of plays by heavyweights such as Thornton Wilder have shown an ongoing appetite for reinterpreting mid-century American drama; Belflower’s work, by contrast, turns an iconic play on its head rather than simply reviving it.

The commercial gamble is not insignificant. Broadway audiences often flock to big-name revivals or musicals rooted in familiar stories. John Proctor Is the Villain merges that familiarity with an undeniably modern perspective, offering both the name recognition of The Crucible and the excitement of fresh thematic ground. Early word-of-mouth from regional and amateur productions—where the play received accolades for its pointed critique and witty dialogue—suggests that audiences are ready to grapple with the provocative thesis of Belflower’s title.

Teenage Perspective

Belflower’s nuanced portrayal of teenagers is central to the play’s impact. Rather than casting them as naive or one-dimensional, she endows them with a sense of agency, emotional intelligence, and humor. They’re not just earnest do-gooders, nor are they hardened cynics. They reflect the complicated reality of being a teen in 21st-century America: aware of social injustices, yet unsure how to address them; eager to parse moral gray areas, yet uncertain whether the adult world will genuinely listen to their perspectives.

Their in-class discussions mirror the seriousness with which young people today approach questions of gender and power. They discuss whether Proctor’s moral confusion justifies his behavior. They debate the motivations behind Abigail’s actions, and whether historical context excuses or condemns them. In strikingly authentic scenes, they swap rumors about their own personal dramas, bridging the gap between the 17th-century trials and their modern social realities.

Sadie Sink from the upcoming Broadway production of John Proctor is the Villain—photo by Damon Baker.

Beyond the Classroom

John Proctor is the Villain, also invites reflections on how we teach—and how we learn. Is a single interpretation of a text handed down by a teacher truly sufficient for complex works like The Crucible? Or should classroom readings be an evolving conversation shaped by the insights of new generations?

Many educators acknowledge that the more prescriptive approach—“Here’s what the play means, and here’s how you should feel about John Proctor”—belongs to a previous era of pedagogy. Today, teachers are often more willing to let students discuss, debate, and even challenge canonical literature. The fresh lens Belflower’s characters apply to The Crucible illustrates the richness such dialogues can yield.

Historical Context, Contemporary Consequences

Miller famously wrote The Crucible in response to the Red Scare and McCarthyism, seeing parallels between Salem’s hysteria and the House Un-American Activities Committee. At the time, the moral message was unmistakable: fear and false accusations can destroy lives and communities. Over the years, that theme has broadened to apply to various social and political climates—wherever distrust and moral panic take hold. Yet, the deeply personal and sexual nature of Proctor’s relationship with Abigail has often been overshadowed by these broader allegorical concerns.

In Belflower’s rendition, that relationship is at the heart of the matter. She doesn’t dispute Miller’s take on paranoia and collective hysteria, but she argues there’s another layer that demands our attention: How do we confront an “everyman” hero who abuses a power dynamic and then claims moral high ground? If Miller’s text echoes the story of a society led astray by fear, Belflower’s retelling asserts that we must also look at how a society can be led astray by selectively excusing the failings of certain individuals.

Community and Criticism

As Belflower’s play moves into a larger spotlight, critics and audiences are responding with both enthusiasm and curiosity. Some see the work as a necessary corrective to decades of reading The Crucible through a lens that sympathetically exonerates John Proctor. Others caution that by focusing so intently on Proctor’s private misconduct, one might lose sight of Miller’s broader commentary on political persecution. However, as is often the case in the theater world, the debate is precisely what makes a new production worthwhile: it breathes fresh life into a text that could otherwise risk stagnation.

At the heart of John Proctor Is the Villain is a willingness to interrogate the assumptions we have about who wields power, who suffers when that power is abused, and who ultimately gets to rewrite (or re-read) history. Miller’s original text remains integral to our cultural literacy, but it is no longer a static thing—its meaning shifts when examined under the light of new social paradigms.

A Timely Arrival

The timing of John Proctor is the Villain could hardly be more apt. As the theater world emerges from pandemic-related closures, there is a palpable appetite for works that reckon with societal upheaval and cultural shifts. Audiences have displayed robust interest in stories that speak not just to our collective anxieties, but also to our evolving moral compass. A well-known canon piece like The Crucible—and an iconic figure like John Proctor—offers a perfect touchstone for these larger conversations.

Moreover, with the theater community increasingly aware of issues around representation and equity, a fresh adaptation centering teenage voices—especially young women’s experiences—feels both urgent and inclusive. It acknowledges that the next generation of playgoers (and playwrights, directors, and critics) is not content to passively receive the interpretation of a 70-year-old text. They want to engage with it, question it, and, perhaps, turn its moral architecture on its head.

The Enduring Power of Reassessment

John Proctor is the Villain, reminds us of theatre’s capacity not just to entertain or instruct, but to spark ongoing conversations. It also serves as a testament to the idea that no work—no matter how canonized—should be accepted without question. Indeed, by implicating John Proctor, Belflower challenges us to examine the cultural lens we bring to any number of “heroic” or “tragic” figures, whether in classic literature or contemporary headlines.

For those who’ve dutifully read The Crucible in school and who remember John Proctor as a tormented moral giant, Belflower’s play may feel provocative, even shocking. But that sense of shock is precisely the point: it echoes what it must have felt like in 1953, to see Puritan Salem used as an allegory for McCarthyism, an unsettling reflection of the audience’s own moment. Now, in a very different 21st-century moment, The Crucible remains a mirror, reflecting new facets of the American psyche—and daring us to look more closely at what we find there.

When the curtain falls, theatergoers may find themselves reflecting on The Crucible with an entirely new perspective, one that refuses to let the man at its center off the hook so easily. Maybe that’s the greatest testament to Arthur Miller’s genius: his play continues to speak to us, no matter how drastically the cultural conversation changes. And if John Proctor Is the Villain has its way, that conversation is about to change again, inviting us to confront what we’ve left unsaid for too long.

In all likelihood, we will continue to teach and perform The Crucible for decades to come—but thanks to Kimberly Belflower’s incisive new offering, we may never read it the same way again. And that, perhaps, is what great theater can do at its best: prompt us to rethink not just a story’s protagonist, but our own deeply held assumptions about who gets to define heroism, how we assign blame, and whether “villainy” might lie in the very narratives we once celebrated as timeless.

John Proctor Is the Villain begins performances at Broadway’s Booth Theatre (222 W. 45th Street) on Thursday, March 20th, 2025, for more information or tickets visit johnproctoristhevillain.com.